Sunday Morning Coffee — June 20, 2021 — One Cool ‘Cat

The conventional six degrees of separation would take a multiple of perhaps five or ten to find some commonality between me and a guy called Mudcat.

Consider: Mudcat was 15 years older than me. He’s Black; I’m not.

He was raised in poverty in Lacoochee, Florida, a mill town 40 miles north of Tampa and 50 miles west of Orlando; me in a middle class, whitebread suburban community on Long Island. In Lacoochee the train tracks split the town: Whites on one side, Blacks on the other. On Long Island the train tracks meant the Long Island Rail Road was pulling into the station to whisk us 40 minutes in comfort into New York City. In Lacoochee the Blacks had their own restrooms and water fountains. So did the Whites. On Long Island we went anywhere we wanted to go.

We both grew up surrounded by racism. Mudcat lived it every day of his young life; I flipped by stories about it every day in the newspaper on my way to the sports section.

Mudcat went to an all-Black high school and church because he had to. I went to an all-White high school because there were no Blacks, and an all-White synagogue because Sammy Davis Jr. lived in California. When Mudcat was a kid Lacoochee had a population of 290, three percent of which was his family. Our county on Long Island, Nassau County, was 1.3 million back in the day.

He could sing. He and a sister entertained factory workers on shift change for pennies in a tin can. I couldn’t carry a tune in the proverbial bucket.

Other than that, Jim ‘Mudcat’ Grant and I had a lot in common. Okay, maybe just a little.

We both played high school ball; only Grant was an athlete, I was a slug. For him to play sports in high school meant missing the bus ride home. It was no big deal for us suburbanites as we had non-working moms carpool us the three miles. Grant’s high school was seven miles from home and if he missed the bus it meant either walking or trying to thumb a ride back in time for dinner. For us, dinner was on the table when we arrived.

And we both had nicknames. Grant became ‘Mudcat’ as a teenager, tabbed by a good ole redneck who figured all Blacks were from Mississippi and named him after the common bayou catfish. In my high school years I was ‘Butch’, tabbed by classmates for my affinity for a little-known shooting guard on the Knicks, Howard ‘Butch’ Komives. At summer camp in the 60s I was ‘Bronco’, for my equestrian prowess or more precisely, lack of. Mudcat stuck to Grant. Fortunately, except for a few stragglers to this day, Butch and Bronco did not. No Jewish kids are called Butch or Bronco. Maybe Hymie, Seymour or Abe but not Butch nor Bronco.

Perhaps most important for both of us was our family unit. Mudcat lost his father in 1938 when he was two and his mom became the family staple raising nine kids and working two jobs. On this Father’s Day, I am grateful for my dad who died three years ago at the age of 89. I think of him every day, not only today. He was our family rock, earning a living working long hours in the Fulton Fish Market in New York City while Mom stayed at home trying to keep my brothers Mike, Ken and me in tow. We had it good. Mudcat would say likewise.

What brought Mudcat Grant and me together was baseball. It’s what brought Mudcat Grant and a lot of kids like me together. He played it at the highest level. The rest of us watched and worshipped the game and its heroes from the bleachers, jealous we couldn’t be them.

Grant, 85, died last weekend at his Los Angeles home. Somehow during his last five years, though only barely, our lives became intertwined.

A 21-game winner in ‘65.

Mud pitched in the big leagues for 14 seasons from 1958, as a $3,500 a year rookie for Cleveland, until he retired in 1971 as an Oakland Athletic earning $52,500, putting him in an exclusive Lacoochee tax bracket. In between he played for five other teams — Minnesota, Los Angeles Dodgers, Montreal, St. Louis and Pittsburgh. He won 145 games in his career, losing only 119. A 3.63 ERA and 1,267 strikeouts. He was a two-time All-Star. His banner year with the Twins was 1965 going 21-7 to become the first Black pitcher in the American League to win 20 games. He would have been a shoo-in for the Cy Young Award as the league’s best pitcher. However, back then they only awarded one Cy Young, not one for each league like today. Some guy named Sandy Koufax went 26-8 that year for the Dodgers pitching with a bum elbow and took the gold. The Twins and the Dodgers, and the two top hurlers in the game, met in the 1965 World Series.

Grant’s road from the dirt of Lacoochee to the dirt of the World Series pitching mound was by no means a smooth one. Fighting off poverty and knowing no better as a kid, he was a high school phenom in football and baseball. In 1952 Florida A&M University in Tallahassee gave him a scholarship to play both football and baseball. He stayed for a year but eventually Mud had to quit school to go back home and work as a carpenter’s apprentice to help make ends meet for his mom and eight siblings.

After leaving college, the Cleveland Indians remembered him from the state Negro Baseball Tournament a few years earlier and signed Grant to a contract. Bonus money? Zero. “They didn’t give me a dime because they didn’t have to,” Mud remembered. “In those days they signed you as a ballplayer with no specific position and if you were good enough to make it out of rookie camp, you made a few dollars. If you weren’t, the team wasn’t out anything. I was just happy to sign and have a chance to be a baseball player.”

Grant was a third baseman and had a pistol for a right arm. By the time the Indians rookie camp in Daytona Beach ended, he was in the pitching group. He took a crash course in pitching from the great Satchel Paige and Cleveland liked him so much they signed Mudcat to a minor league contract for $250 a month, qualifying him as one of the richest men, if not the richest, in Lacoochee.

Grant should have been sent to the Indians entry-level Class D team in Tifton, Georgia. Tifton, as racially segregated as it sounds, was no place to send a young Black man. Instead, Cleveland moved him up a notch to Class C in Fargo, North Dakota, as polar opposite Tifton as one could find.

“When I got to Fargo I was nineteen years old and for the first time in my life I could eat in a restaurant and go to the restroom as a free person,” Grant told me. “The kids there hadn’t seen many Black people and they were great to us. My life was finally one of freedom. I was playing the great game of baseball. Fargo was wonderful!”

The year was 1954 and Grant won 21 games that season. He steadily moved up the Cleveland chain earning his major league roster spot and his first big league start in 1958. He went nine innings against Kansas City, gave up eight hits, striking out five in a game Cleveland won 3-2. The pride of Lacoochee was on his way to a long major league career.

I had never met Mudcat Grant. Not officially anyway. I was with him once, exactly 50 years ago, as a kid seeking an autograph. Forty-five years later we got formally introduced over the telephone. I don’t remember who brought us together; it was either an official from the Twins or the Indians, I forget. The good news for me however is I do remember what I had for breakfast yesterday.

When I planned my second book, Big League Dream (bigleaguedream.com or on Amazon using keywords ‘Roy Berger books’), because my experience at various baseball fantasy camps was so wonderful, I wanted to try and bring the baseball fan and the guys who were so instrumental in our childhood as major leaguers, together. The perfect mix for me was a selection of ex-pros who now devote a week or two a year to guys like me at respective team camps. For a week we can pretend to be what we were not, and they help us with our dream considering they once lived it.

Big League Dream spans a spectrum of players most of us on Medicare remember: Bucky Dent, Ron Swoboda, Maury Wills, Jake Gibbs, Kent Tekulve, Dennis Leonard, Big John Mayberry, Mike LaValliere, Fritz Peterson and Chris Chambliss. Also those long forgotten like Steve ‘Psycho’ Lyons, Gary Bell and the funniest man in baseball, Jon Warden. The book even weaves in a chapter on the greatest hockey announcer ever, Doc Emrick, who grew up wanting to be a Pittsburgh Pirate and got to live his dream at Pirates fantasy camp a number of years ago.

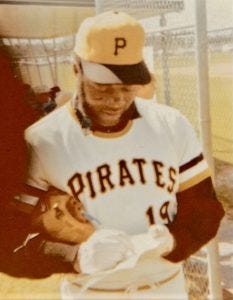

Signing for me in 1971.

When the opportunity to speak with Mudcat was offered to me, I didn’t hesitate. I remembered him well. He signed an autograph for me in 1971 in Bradenton, Florida, when I visited Pirates spring training. Why I still have that picture, other than it’s me being me, I don’t have any idea. We were together maybe 15-20 seconds. I remember his smile. Incredibly, I still have the Pirates spring training roster that he, along with Roberto Clemente and Willie Stargell, signed that day. Then, Mudcat Grant was just another baseball player giving a few seconds of his time to sign a sheet of paper. Like many spoiled and naive suburbanite kids, I had no idea of his struggles to make it in life and baseball. To me, everything seemed easy. To Mud, it was anything but.

In mid-2016 we spent maybe four or five hours over a couple of days talking on the phone for the book. He was in an easy chair in his Los Angeles home, his wife of over 40 years, Gertrude, by his side. Grant was ailing, diabetes taking a toll on him, getting around with a walker and cane but in wonderful spirits. Like most of the old timers, he loved telling stories. Mudcat had a way of putting his own verbal exclamation point on his words at key moments. To say he was engaging is like saying Ted Williams could hit a fastball.

Mudcat is the first of my Big League Dream book subjects to pass. When I first heard about it last weekend I went and re-read the chapter we did together. I smiled again. He was so proud of so many things he accomplished, not the least of which was staring racism in the eye and having a successful career in spite of his travails. I was reminded of the joy he exhibited when speaking about his post-baseball career as an entertainer: the man could still sing, and his 1965 World Series celebrity opened many show business doors for him including guest spots on The Mike Douglas Show and multiple appearances on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson. After baseball he formed a group, Mudcat and The Kittens, five scantily clad women, who toured the world including a gig at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas. He sported mutton chop sideburns, a leisure suit and the mandatory open silk shirt. A reviewer called him “mod.” That’s sorta like being “really cool” today.

“I made more money with my music than I did in baseball,” Grant proudly said.

Years later, Mudcat makes a triumphant return to Lacoochee.

He also became an author with his publication of The Black Aces, a 2006 profile of 13 Blacks who won 20 or more games in MLB and ten pitchers from the Negro Leagues who Mud believed would have also achieved that status in the bigs if they were afforded the chance. President George W. Bush, a huge baseball fan, so loved the book that he personally called Grant and invited him to the White House. Needless to say the road from Lacoochee, Florida, to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue is not well traveled.

I loved Mudcat telling me the story of the opening game of the 1965 World Series between his Twins and the Dodgers. He was so proud, yet also disappointed.

There was no doubt the Twins were going to give the ball to their 21-game winner. For the Dodgers, the logical starter was 26-game winner Koufax. The two best pitchers in baseball.

“Before the game started, I stood on the mound for a few minutes and thought about all it took for me to get to that point” Grant remembered. “This is the World Series and I thought about Larry Doby and Jackie Robinson and Luke Easter and all the others that sacrificed so much so I could have that opportunity and moment.”

Mud’s disappointment was Sandy Koufax wasn’t on the hill for the Dodgers as planned. Game 1 was played on October 6, 1965, which was Yom Kippur. Koufax, an observant Jew, would not play on the holiest day of his religious year.

“We were about to make baseball history,” Grant recalled. “Even though I knew two days before Sandy wasn’t going to pitch, it would have been the first time, and maybe the last time, that an African American and a Jewish starter opposed each other in the World Series.”

Instead, the Dodgers went with Don Drysdale, no slouch himself with 23 wins that season. It wasn’t much of a contest with Grant and the Twins beating the Dodgers 8-2, but it did produce one of the greatest wisecracks in baseball history.

The Twins put the game away early scoring six times off an ineffective Drysdale in the third inning. When Dodgers manager Walter Alston took the slow walk to the mound to pull his starter, Drysdale flipped the ball to Alston, and before walking off muttered, “I bet you wish I was Jewish, too.”

Mudcat loved to tell that story. Mudcat loved to tell any story. To his dying day, Mudcat also loved to sing. With Jim Grant now up above, nights around the campfire will never be dull.