Sunday Morning Coffee — August 18, 2024 — Cruisin’ With A Byrd

Roger McGuinn had an amazing career. He is as humble about it as he is accomplished. He is as accomplished as he is humble. And at 82, he’s not finished.

McGuinn is a professional musician. Perhaps you know of him. You definitely know his music. In fact, he now spans all generations. We Boomers were lucky enough to listen to him in his prime; the younger generation, as long as they have a debit card and a satellite radio subscription, now know his music as well.

McGuinn was the co-founder, frontman and leader of the great 1960s folk rock group the Byrds. Though not together for very long, they had a lasting impact on music and music history that will live for the ages.

A special bonus to our cruise across the pond from London to New York a few weeks ago on Cunard’s QM2, McGuinn was on board as a guest lecturer. He did three one-hour seminars in a series, on Monday, Wednesday and Friday, each was a continuation of the previous one. It was fascinating and for me, and our generation, turned out to be absolutely must see.

I love history – music, comedy, politics, sports – reliving those days and eras and learning so much now that I never knew then. You especially have me with vintage video, black and white preferred. McGuinn’s reel was right in my wheelhouse starting in 1962 when he worked with Bobby Darin as a back-up guitarist, harmony singer and eventually the folk music component of Darin’s act. Plus classic footage of Dick Clark, Ed Sullivan and a bunch more.

A great three hours listening to McGuinn aboard ship.

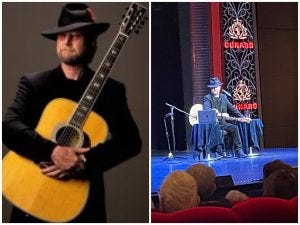

McGuinn made himself comfortable on stage. Dressed in Johnny Cash black with a matching fedora and a red side feather, guitar readily accessible and a laptop to move his own slides, videos and graphics. Soft spoken but authoritative. He was anything but impressed with himself. We all felt differently.

McGuinn’s love of music started at age 13 with a transistor radio and AM frequencies in his Chicago home. The next year, 1956, inspired by Elvis’ Heartbreak Hotel, he asked his parents to buy him a guitar. He taught himself how to play. As a bonus he joked, “All of sudden the girls liked me better.” A year later, at age 15, McGuinn enrolled in Chicago’s Old Town School of Folk Music learning to play a borrowed banjo and what became his musical trademark— a 12-string guitar.

McGuinn’s lectures and songs during our voyage were in the ship’s main showroom, the Royal Court Theater. Seating about 1,100, the space was probably half full. Competition on the ship was fierce for the other 2,000 cruisers: chairobics, beginning bridge lessons, morning trivia, a darts tournament and the always scintillating ‘Line Dancing with Phoebe & Joe.’ Never mind those who queued up an hour early for the lunch buffet hoping to get first crack at the sushi.

After graduating the School of Folk Music in the early 60s, McGuinn’s career took him back and forth from New York and Los Angeles. He was hired as an accompanist for the Limeliters, the Chad Mitchell Trio and Judy Collins while trying to develop his own portfolio.

When not doing back-up work he performed solo at LA’s The Folk Den, the forerunner for what became the famed Troubadour nightclub in 1964. At the same time McGuinn was infatuated with the upstart Beatles and their music. It prompted him to take his folk music and incorporate a rock ‘n roll sound like the Beatles. Another folkie Beatles fan, singer-songwriter Gene Clark, teamed up with McGuinn at The Troubadour. A few months later David Crosby joined the act. Then Chris Hillman and Michael Clarke came aboard. The combo dubbed themselves the Jet Set.

Enamored by I Want To Hold Your Hand, the Jet Set dressed like the Beatles; had mop tops like the Beatles. Drummer Clarke had to have a Ludwig kit like Ringo. McGuinn bought a 12-string Rickenbacker guitar, the same as George Harrison played. It ultimately became McGuinn’s musical trademark.

The newly assembled group got their first break in late 1964 when they received a disc of Bob Dylan’s Mr. Tambourine Man which Dylan decided not to release because he wasn’t happy with its sound. When Dylan heard the Jet Set demo, he gave it his ringing endorsement.

Two weeks before Thanksgiving, the band signed a recording contract with Columbia Records upon the recommendation of the great jazz trumpeter Miles Davis. Mr. Tambourine Man had not yet been released and in the interim the band soured on the Jet Set moniker and searched for a new identity. In Los Angeles for Thanksgiving they sat around the table looking at the turkey. Someone suggested they should call themselves the Birds. McGuinn told us they liked the name but not the spelling. “In England a good looking woman was called a bird. We were far from being birds.” Someone else suggested changing it to the Burds but McGuinn said if they bombed “we would be known as The Turds.” Finding nothing wrong with the Byrds, it stuck.

The Byrds: front (l)- David Crosby and Jim (soon to be Roger) McGuinn. Rear (l)- Chris Hillman, Michael Clarke and Gene Clark.

Mr. Tambourine Man was finally released in April 1965 and by June became the number one record in both the US and UK. On England radio, the Byrds were billed as America’s answer to The Beatles. The Fab Four also took a shine to the Byrds, becoming both fans and friends calling them their favorite American act. They also partied on more than one occasion together.

The Byrds second number one hit, Turn! Turn! Turn!, was a composition by Pete Seeger in 1959 and recorded three years later by the Limeliters with whom McGuinn played back-up. The lyrics consist of the first eight verses of the third chapter of the biblical Book of Ecclesiastes. When the Byrds version was released on October 1, 1965, it skyrocketed to number one. That landed them the very coveted appearance as musical guests on The Ed Sullivan Show. Their December 12, 1965, slot (on YouTube) was the first and only one for the band who sang both Mr. Tambourine Man and Turn! Turn! Turn! They shared the stage that night with Al Hirt, Alan King, Wayne Newton and Barbara McNair. Yes, it was a really big show.

When the Byrds sang their hits on the Sullivan show, they actually didn’t sing them. That was the era of lip-syncing — show producers wanted to get the best audio possible. TV studios were not built as sound stages and there were concerns about proper miking and mixing. The only group that didn’t lip-synch were the Beatles — there was so much screaming when they performed nobody could hear the music anyway.

As McGuinn told us, “Lip-syncing was really a joke. You sang your own songs but the mics were turned off, so you were really moving your mouth to the music. Our words couldn’t be heard, just the recording that played.”

Things began to unravel for the band over the next couple of years. There was reported increasing tension and acrimony among the group. Competition was fierce for writing and recording credits. The sound of the group changed in early 1966 when they recorded what was dubbed the first psychedelic rock tune called Eight Miles High. McGuinn was on lead guitar, but the song was banned by many US radio stations following allegations the lyrics promoted recreational drug use. Despite its limited play, the controversy helped get the record as high as number 14 on the charts.

The breakup began in early 1966 when Gene Clark left allegedly due to a fear of flying. McGuinn factually told him “If you can’t fly, you can’t be a Byrd.” Drummer Clarke (with an ‘e’) quit in 1967 not pleased with the songwriting material his bandmates were supplying. Two months later David Crosby left allegedly driven by his ego and dissatisfaction with the band’s musical direction. McGuinn was more diplomatic telling us that Crosby moved on because “he wasn’t getting his records recorded.” Crosby wasn’t out of work long, soon teaming up with Stephen Stills and Graham Nash.

Once the original Jet Set/Byrds disbanded, late ‘67, early ‘68, McGuinn tried to patchwork other bands and other musicians into the sound, but never could resurrect the short yet profound years of the Byrds. Industry media called them ‘one of the most influential bands of the rock and roll era.’ While there were scatted reunion attempts, nothing stuck. Promoters tried to bring back the band for Woodstock in 1969. However, according to McGuinn, “rumor had it you wouldn’t get paid so we all decided to just keep whatever individual engagements we had for the weekend.” Woodstock was 55 years ago this weekend.

And then there was one magic evening, on January 16, 1991, the night the Byrds were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. The original five came together and wowed the audience with Mr. Tambourine Man, Turn! Turn! Turn! and I’ll Feel A Whole Lot Better, which everyone did witnessing their final performance.

McGuinn embarked on a solo and freelance career. He changed his name from Jim to Roger in 1967 when he became involved in the Subud interfaith spiritual movement. He tried to explain it to us, even showing a clip from the David Letterman Show, but I’m certain nobody understood, not the least of whom being Letterman who quipped, “Yep, Roger sure is a spiritual name isn’t it?”

His 1969 solo version of the Ballad of Easy Rider became a classic in the Peter Fonda film. He played back-up on Simon & Garfunkel’s 1966 Sounds of Silence taking a busman’s holiday from the Byrds.

The great video he played for us was from 1992 in Madison Square Garden. It was Bob Dylan’s 30th Anniversary Concert Celebration. McGuinn’s contribution to music over the preceding three decades earned him stage time with George Harrison, Eric Clapton, Tom Petty, Neil Young, Kris Kristofferson, Stevie Wonder, Lou Reed and of course, Dylan. As he narrated the clip, it was the first crack in McGuinn’s humble armor — how proud and honored he was to have been a part of that all-world collection of musicians.

These days he’s touring — playing clubs and smaller concert halls for his very intimate and personal show. (Dates and availability are on Ticketmaster.com) It’s well worth an evening out if he’s at a venue near you.

And if for some reason you weren’t familiar with Roger McGuinn before today you no doubt know him from the Mamas & the Papas 1967 ballad Creeque Alley. It went like this:

McGuinn and McGuire just a gettin’ higher in LA, you know where that’s at, and no one’s gettin’ fat except Mama Cass.

McGuire was Barry McGuire known for his moving and ultimately perceptive 1965 hit Eve of Destruction.

During McGuinn’s Q&A session on the ship someone asked what that refrain actually meant.

“I don’t know,” he chuckled. “Maybe because we both had number one hits so that’s why we couldn’t get any higher. But I’m guessing it was meant to be a double entendre.”

As high as McGuinn and McGuire may or may not have been, it couldn’t match the euphoria all of us who sat through the three stimulating hours on the ship with Roger McGuinn experienced. And ultimately none of us felt bad about missing Line Dancing with Phoebe and Joe.