Sunday Morning Coffee — January 24, 2021 — “Someone Was Going To Throw That Home Run Pitch”

If Hank Aaron would have broken Babe Ruth’s career home run record at any time other than a Monday night or a Saturday afternoon most of the country would have found out about it the old-fashioned way— in the next morning’s newspaper.

In 1974, five years before ESPN and six before CNN, when television sets still had rabbit ears, we got our news, weather and sports at 6 or 11 in the evening or in print the next day.

Baseball got lucky. NBC got lucky. We got lucky.

NBC, beginning in 1966, had the Major League Baseball contract to broadcast the “Game of the Week” which was every Saturday afternoon when Curt Gowdy and Tony Kubek paid us a visit. For markets that did not have a big league team this was the only televised game they were able to watch. NBC then added a Monday night national game to help sagging summertime ratings. Baseball was still America’s sport. The game might have been slow but so was life. The public liked it and NBC extended the Monday night agreement to 15 games starting with the 1973 season.

April 8, 1974 was a Monday night. It wasn’t scheduled to be an NBC broadcast night but Hank Aaron made it so. NBC’s regular Monday night feature was Monday Night at the Movies; giving it the last-minute heave-ho wasn’t too tough of a call.

The Braves opened the 1974 season on April 4 at Cincinnati. They lost 7-6 but that wasn’t the story. Hank Aaron hit his 714th career home run in the first inning off Jack Billingham to set the stage. In baseball’s long and glorious history only one other player had ever hit that many home runs in a career. And Babe Ruth was no ‘other’ player. He was royalty. He was ‘The Babe’.

The city of Atlanta held its breath. While they never rooted against Aaron, they rooted against him that weekend in Cincy. The Braves were coming home on Monday to face the Dodgers; if there was to be a new home run king, Atlantans wanted to see it happen on their turf. Aaron had three more at-bats on opening day with no other hits; he didn’t play game two on Saturday and was 0-3 on Sunday. Perfect. The Braves were headed back to Peachtree Street.

The anti-Aaron hate mail and death threats intensified. The language got raw. Hank Aaron was a Black man from Alabama, playing baseball in Georgia, about to dethrone a good ole’ hot dog loving, cigar chompin’, chubby playboy, who was loved by white America. How dare Hammerin’ Hank?

Big league veteran Al Downing wasn’t scheduled to pitch for the Dodgers that Monday night. “Tommy John was supposed to pitch for us, but his elbow was bothering him so (manager Walt) Alston asked me to start,” Downing told me a few weeks ago when we were chatting for the December 20, 2020, Sunday Morning Coffee, “The Music Man.”

For every great and memorable home run in baseball history, someone is remembered as a trivia answer for tossing it. Ralph Branca teed it up for Bobby Thompson; Ralph Terry put the ball on the sweet spot of Bill Mazeroski’s bat and Dennis Eckersley threw a lame Kirk Gibson the ball he planted in the right field bleachers. Jack Buck did not believe what he just saw. Neither did we. There have been dozens more.

No seat was empty in Atlanta on April 8, 1974. That was very unusual for a Braves home game. Nor was there an empty seat in my University of Miami dorm room; I was one of the cool kids with a TV and, more importantly, an antenna that wasn’t bent and even worked. April 8, 1974 was almost 20 years to the day after Aaron’s major league debut as a Milwaukee Brave. All 53,775 Aaron fans booed loudly when Downing, only sixty feet, six inches away, walked their hero leading off the bottom of the second.

“Listen, I knew what was going on,” Downing laughed. “If I threw him a fastball he wasn’t going to miss it, especially from a left hander, so I tried to get cute but wound up walking him.”

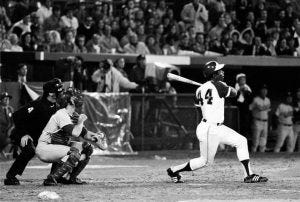

Aaron’s second at-bat was in the fourth inning. Dodgers catcher Joe Ferguson crouched behind the plate with umpire Shag Crawford over his left shoulder. Downing’s first pitch was in the dirt. The booing got louder. Braves slugger Darrell Evans was on first. Downing got the sign from Ferguson. For some reason Ferguson put down one finger for a fastball. Downing, seasoned at 32, didn’t shake him off. Downing went into his left-handed stretch and looked at Evans who had a small lead off first. Evans, with the speed of a keg of Pabst Blue Ribbon, wasn’t going anywhere.

Aaron cracks #715 off a Downing fastball.

The 40-year-old Aaron liked what he saw. His compact, wristy swing connected perfectly with the Downing fastball. It was high and deep. Dodgers left fielder Bill Buckner, yes that Bill Buckner, tried to scale the left center field fence and nab it. Instead, the ball landed in the glove of Braves reliever Tom House in the Atlanta bullpen. There was pandemonium in Dixie! Fans rushed onto the field. So did House from the Braves ‘pen to bring the ball to Aaron as he crossed home plate. Stadium security must have been on break because there was no crowd control. There was every reason to be scared for Aaron’s safety. Fans were all over the field trying to touch the new sultan of swat. Dodgers second baseman Dave Lopes and shortstop Bill Russell high-fived him as Aaron trotted past. So did third baseman Ron Cey. Aaron was mobbed at home plate by teammates and more fans. The king is dead; long live the king.

Downing didn’t feel bad. Far from it.

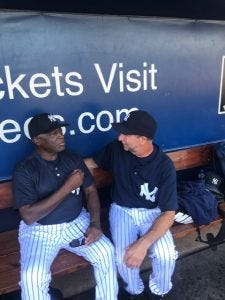

Getting another baseball history lesson from Al Downing at Yankees camp.

“Someone was going to be the one to throw that home run pitch,” Downing recollected. “I would have much rather got him to pop out, but I knew it was an historic moment and to tell you the truth, I am proud to be a part of it. Let’s give credit where credit is due— it was magnanimous.”

Downing continued: “I had a great deal of admiration for Hank Aaron. He is a very proud man and rightfully so. He never complained. Never argued with anyone. You always treated the man with respect, and he gave you that respect right back.”

Legendary Dodgers announcer Vin Scully did the play-by-play that night. Only ten years earlier, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act theoretically ending the discrimination that plagued Aaron his entire career. “What a marvelous moment for the country and the world,” Scully bellowed as only Vin could do with the exclamation point, “A Black getting a standing ovation in the Deep South!”

Hank Aaron retired two years later. His record of 755 career home runs was broken, with an asterisk, by Barry Bonds in 2007. Most speculated Bonds’ performance was enhanced by artificial substances. Mr. Aaron felt drug and steroid use to enhance performance was inappropriate in the sport. However, after Bonds hit his 756th career home run, there was a video shown on the San Francisco scoreboard of Aaron congratulating Bonds. It was typical Aaron class.

Hank Aaron died on Friday at the age of 86. No finer gentlemen ever walked between the white lines. His 755 home runs are second all-time behind Bonds with the asterisk. His 2,297 RBI is the best ever. His 25-time All-Star appearances the most ever. He was a 1957 World Series champion and inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1982. To his dying day, Aaron was a part of the sport as an ambassador for the Braves and the game of baseball.

Hank Aaron may be gone but his legacy, like The Babe, will live forever.